A Winterreise Hypothetical

Müller vs Schubert in Der Leiermann

In the twenty-four poems of Wilhelm Müller’s Die Winterreise the protagonist gives expression to no fewer than twenty-six questions. According to the ordering of the poems in Franz Schubert’s Winterreise song cycle, the first twenty-four of these questions are scattered among twelve of the first twenty-one songs and are rhetorical in nature, being addressed by the protagonist either to himself or to the world at large. These questions reflect the thoughts and feelings of the jilted lover, being focussed first on self-pity (Nos. 1-13) and then on the desire for death (Nos. 14-23).

In the final poem – No. 24 Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man) – there is a total shift in the poetic psychology. Whereas the first twenty-three songs give expression to a self-absorbed psychopathological journey entirely void of human contact – and almost void of any living creature at all save for occasional references to barking dogs, hostile ravens, a fond memory of a lark and nightingale engaged in competitive song, and a portentous crow – No. 24 is devoted completely to the woeful plight of someone other than the protagonist. For the first time in the entire cycle, the protagonist focusses on the pathetic situation of another human being – a pitiful, lonely hurdy-gurdy man to whom nobody listens, from whom everyone averts his or her gaze, and whose little plate is always empty as stray dogs growl around him, thus:

- The Hurdy-Gurdy Man1

| Stands an organ-grinder There outside the town, Plays as best he can though Fingers stiff have grown. |

No one likes to hear him, No one looks his way, And around the old man Stray dogs growl and bay. |

| Barefoot on the ice He totters to and fro, And his little plate Stays empty always so. |

And he lets it happen, Always, as it will; Plays his hurdy-gurdy And is never still. |

|

Hey, you strange old fellow!

Should I with you go? Will you play your organ To my songs also? |

|

Let us put aside, for one moment, Schubert’s musical setting of this poem and focus instead on what Müller’s intention was in introducing such a seismic shift at the end of his poetic cycle. What is Müller actually telling us in this final poem?2 I find it hard to imagine that this sudden and totally unexpected focus on the hurdy-gurdy man is intended to be anything other than an opportunity and possible occasion for the protagonist’s redemption. The poet brings this opportunity into the picture just in the nick of time, just before the ultimate fulfilment of the erstwhile suicide’s fervently nurtured death-wish can occur.

The imagery is clear enough – the protagonist suddenly realises that there can be someone in the world worse off than himself and this realisation has a twofold effect: firstly, it makes the protagonist’s own woes seem trivial by comparison; secondly, it offers the protagonist the opportunity to engage in the redemptive, life-affirming task of helping others. In this way, the whole poetic cycle created by Müller concludes, not in the long-sought death of the protagonist, but with his offering of hope to the miserable street musician, asking whether the two might now join forces and make music as they travel together.

Because Müller allows these concluding questions to remain unanswered, we are left free to speculate on the outcome. Will the musician accept the offer of companionship and collaboration or will the protagonist encounter yet another rejection? While we cannot answer this with certainty we might fairly suppose that the protagonist is already redeemed: he has been liberated from the psychopathological bondage that has afflicted him from the outset of the cycle, and he is now able to put his own suffering in perspective and seek to help others less fortunate than himself. Thus Müller, in this final verse of the final poem, produced a veritable sting-in-the-tail for the whole cycle. He has allowed the protagonist a last-minute reprieve which immediately raises the possibility of a new beginning.

Let us now bring Schubert’s music back into the picture and ask ourselves whether such a sting-in-the-tail is to be found in the setting of the final verse. Schubert’s music for No.24 reflects most starkly the physical and psychological bleakness of the scene. In this final song, neither tread nor pulse is detectable. The protagonist has reached the end of his journey and the music has become still, hollow and lifeless – the apotheosis of futility. The piano part is marked pianissimo almost throughout, punctuated here and there with faint accents and swells. As the vocalist’s final note is held softly, a sudden loud entry of the accompaniment signals the protagonist’s final convulsion and collapse. Schubert thus confirms that the long-awaited, fondly sought end has come at last, thereby answering the protagonist’s two questions in the negative.

It is not difficult to find reasons why Schubert might have chosen to do this. The tenor Ian Bostridge3 has described (p.480) “Schubert’s awareness of his own prognosis – the terrifying fate of the syphilitic, the inevitable physical and mental deterioration” at the time of composition of Der Leiermann; it is understandable that in such circumstances Schubert might overlook – or be disinclined to engage with – other, more positive, meanings for Müller’s final poem. Thus, the psychological gear-change inherent in the poem, particularly in its final verse, is not to be found in the song.

All of which leads me to propose this hypothetical – what if Schubert had been more inclined to explore the gear-change of No. 24 in a more positive way? How might the music have differed from what he left us? I suggest two possible answers here by making changes to the piano part in the final bars. Both of these changes – one very minimal and the other quite substantial – pay due respect to the unanswered nature of the questions in the final verse by leaving the closing cadence unresolved.

My impulse for putting together this hypothetical stems from two points of departure. The first of these is a strong conviction developed in relation to No.24 over the past fifteen years in rehearsing, performing and recording Franz Schubert’s Winterreise. It has long seemed to me that, in choosing to end No.24 with a perfect cadence, Schubert injected more finality into the conclusion of his song cycle than Müller injected into the conclusion of his cycle of poems.

The second point of departure arises from a gentle artistic ‘tug-of-war’ that occurred during a 1979 rehearsal between baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and pianist Alfred Brendel concerning the dynamic shape of the vocalist’s final note in Der Leiermann. This was captured in a video4 of the rehearsal in which Fischer-Dieskau first makes a strong crescendo swell on this final note in sympathy with the pianist’s loud entry. There follows a conversation in which Brendel suggests that the vocal line should remain very soft with no crescendo while the piano alone makes a loud entry and swell at bar 58. The musicians then render the passage according to Brendel’s suggestion. However, in the final recording, Fischer-Dieskau makes a moderate swell on this final note – a kind of non-descript compromise between his first instinct and Brendel’s suggestion.

I believe that such uncertainty concerning the appropriate rendition of the vocal line in bar 58 is an unavoidable consequence of Schubert’s own construction of this song which I find to be somewhat unsupportive of the general intent of Müller’s final verse comprising two unanswered non-rhetorical questions.

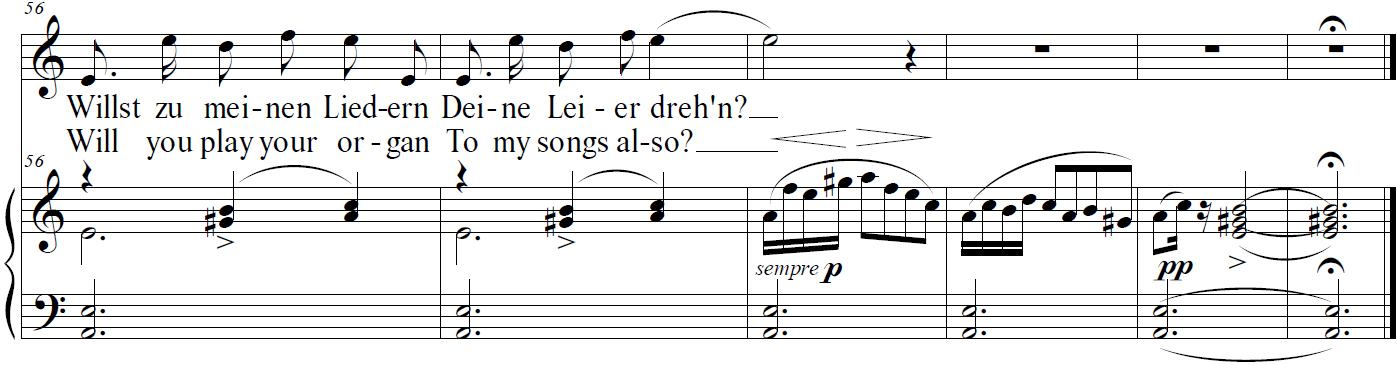

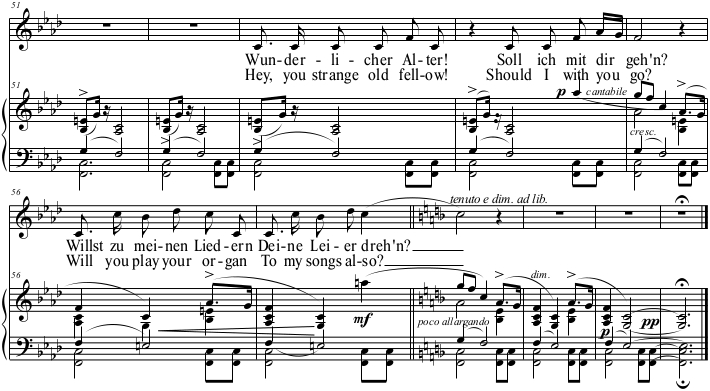

A minimal solution to this situation might be found by replacing the forte directive at bar 58 with a sempre piano directive and leaving the final cadence unresolved, thereby giving due acknowledgment to the unanswered nature of Müller’s questions, thus (high-voice version):

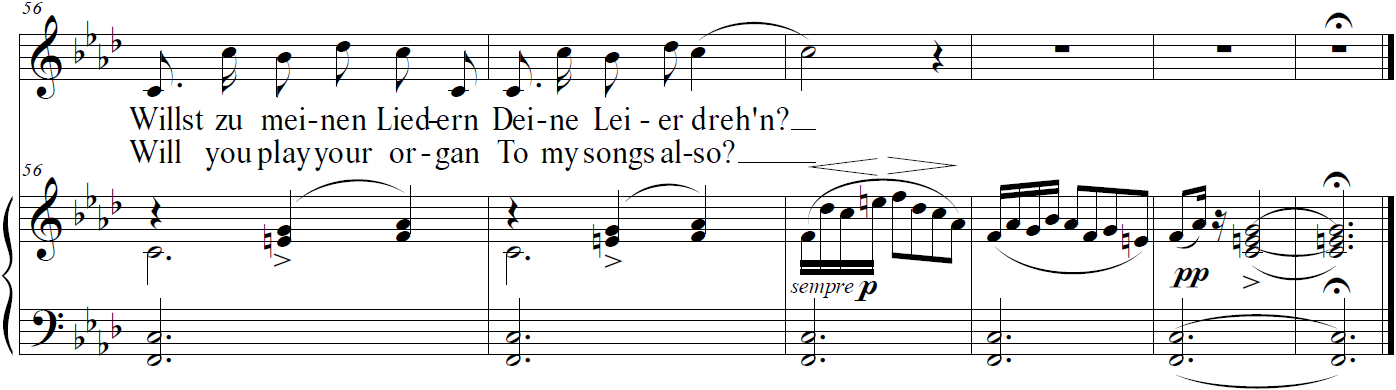

or thus5 (low-voice version):

Allowing the piano part to continue softly at bar 58 removes the suggestion of sudden collapse and death, while removal of the tonic resolution of the right hand piano part at bar 61 reinforces the lack of any firm answer to the two questions as the music peters out in bleak emptiness.

Moving on from the above minimal suggestion, the possibility of an alternative meaning for the end of No. 24 is implicit in another statement by Bostridge that (p.475) “such a vision of true indigence at the very end of the cycle is bound to raise at least a small question mark over the self-indulgence of endlessly perpetuated, inner-directed pain.” As described above, I have gone further and suggested that the final verse of Der Leiermann affords a redemptive idea that brings about the will to live and the possibility of engagement with more life-affirming pursuits.

I believe that this meaning can be expressed musically in a Schubertian manner within this context. The revision suggested below has been created in two ways:

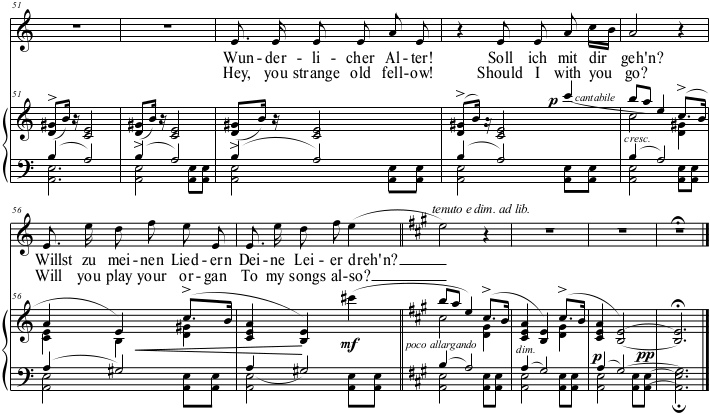

(a) by altering the final 10 bars of the piano part to introduce a shuffling tread and pulse in the left hand for the entire final verse, and

(b) by adapting the theme from No. 1 Good Night for the right hand as the vocalist completes the first question, using warmer dynamics and thereby closing the musical cycle with an echo of its opening. The optimism implicit in this possibility is strengthened via a late change to the major key on the vocalist’s final note while the bare-fifth drone of the hurdy-gurdy remains unaltered in the left hand.

However, this possibility of a ‘happy ending’ remains just a possibility, unresolved in deference to the unanswered questions, thus (high-voice version):

or thus (low-voice version):

Of course, any attempt at re-composition of even a small part of such a highly revered masterpiece might be judged as being grotesquely inappropriate, especially as it is predicated in this instance upon what might be seen as an implied criticism of Schubert’s setting of the final verse of Der Leiermann. However, while respecting such judgment, I find this closing verse of Müller’s Die Winterreise to remain wide open to interpretation as suggesting either the reality of a positive new beginning for the erstwhile hapless Wanderer, or the deluded fantasy of such a beginning; either way, the use of the major key at the song’s end would be justified, given Schubert’s consistent application of major tonality both to actual cheerful imagery and to fanciful illusions thereof throughout the cycle.

In this final verse Müller’s poetic psychology has moved suddenly from negative contemplation to positive action. My offered re-composition of verse 5 is simply one suggestion – among many possible alternatives – as to how Müller’s sting-in-the-tail might have turned out if Schubert had not decided to leave it musically unremarked and undetectable.6

[1] From the 2018 English translation by Brian Chapman published in Low-Voice and High-Voice Editions of the full vocal score of Winterreise/Winter Journey by Australian Scholarly Publishing.

[2] Despite the slightly different ordering of poems and songs between Müller’s and Schubert’s respective cycles, Der Leiermann is the concluding work in both cycles.

[3] Bostridge, I., Schubert’s Winter Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession, London, Faber & Faber Ltd, 2015.

[4] The recording was made by Sender Freies Berlin in 1979 and released as a DVD on the TDK label in 2005.

[5] This alternative ending has been included as Track 25 on a 2019 recording of Winter Journey using this new English translation and performed by Nathan Lay (baritone) and Brian Chapman (pianist and translator) on the Move Records label (Move MCD594a).

[6] New recordings of the whole of No. 24 incorporating the above re-composition of verse 5 were made in both English and German by Lay and Chapman in January 2020. The resulting pairs of audio (MP3) and video (MP4) files have been published by Australian Scholarly Publishing in a downloadable e-bundle titled The Hurdy-Gurdy Man: The sting-in-the-tail of Müller’s ‘Die Winterreise’ that also includes this essay together with full vocal scores of No. 24 re-composed as above in both high-voice and low-voice versions.

© Brian Chapman