No such thing as a definitive version

In the spring of 1827 Schubert’s friends gathered to hear him perform his newest songs. They heard at that time the first twelve songs of what we now know as Winterreise. Schubert wrote the subsequent twelve as a continuation later that year, after finding Wilhelm Müller’s complete work. His friends’ initial reaction of shock at the gloomy nature of these songs is well known. But Schubert’s belief that these were the best of him has since been supported both by his friends and, in subsequent years, by the wider musical world.

The two-part genesis of the work seems to me to be reflected in the underlying mood and subject of each part. The first twelve songs feel driven. I say this even though they contain two songs of great stasis: the ‘frozen songs’ – ‘Wasserflut’ and ‘Auf dem Flusse’. Overall the sense is one of a young man forced away. There is desperate haste and urgency – abundantly clear in ‘Erstarrung’ and ‘Rückblick’, of course – which pervade so many of the songs. ‘Der Lindenbaum’ and ‘Gute Nacht’ show the protagonist tearing his eyes away from all he has held dear. Those delicious moments of major-key memory and tenderness are thrust behind him in blind flight, urged by rage and jealousy (‘Die Wetterfahne’). The focus of attention is entirely inward: he seems hardly to notice the living world around him, so pressed is he to get away.

But the second half seems less concerned with flight. We are jolted into this new realm with ‘Die Post’. The young man’s eye travels outward. Other creatures are seen: the postman on his horse, the crow. And the major-key moments seem to belong less now to him. They are the delights of others (‘Die Post’, ‘Im Dorfe’, ‘Das Wirtshaus’) or, increasingly, moments of torturing illusion (‘Die Nebensonnen’). And of course his thoughts, in seeking a destination, turn ever more to death. And death will not have him. Unlike the boy in Die schöne Müllerin, death cannot provide his right fulfilment. But, tormented by his own youth, we leave him restlessly transfixed by a starving old man, meaninglessly turning the handle of an organ. Ignored, lost. In a world torn away from mankind. A living death.

Decisions have to be made when presenting this work. Schubert’s published versions of 1828 result from significant reworkings of earlier manuscript drafts and fair copies, and it is sometimes hard to know whether these were fundamentally at the composer’s command or editorial suggestion. Nevertheless, we have used these versions as the basis for our recording. In particular, the transpositions of ‘Wasserflut’, ‘Rast’, ‘Einsamkeit’ (part 1), ‘Mut’ and ‘Der Leiermann’ (part 2) down a tone (‘Einsamkeit’ a minor third) have been retained, sometimes with regret and always following (often heated) discussion. There are also questions of tempo and style. I’ve heard it said that Winterreise is a baritone work, and ‘just sounds wrong’ with tenor, as though the darker vocal timbres better accord with the melancholy of the songs. Yet such a work only lives through constant re-examination and challenge. True, the mood is dark, but we must remember that this tragedy is one affecting the young. The man is mocked by his youthful vitality. Schubert’s approaching death was not coming in ripe old age. There’s rage here and determination. The tread of ‘Gute Nacht’ has great purpose and is no dragging plod.

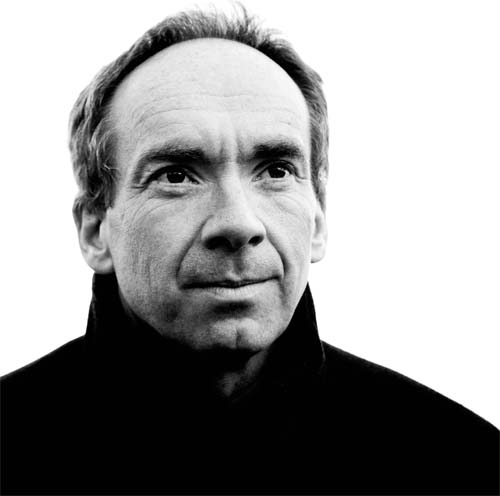

This astonishing work has been much recorded and Anna Tilbrook and I are extremely lucky to have this opportunity to put down our performance as it is at the moment. It has developed over the years through so many performances, and been touched, I hope, by all of them. Different venues, different pianos, ourselves bringing our changing lives, and above all different audiences, each bring their own special subtleties and qualities which suffuse and give meaning to the work through each subsequent outing. There is no such thing as a definitive version. The work lives anew every time minds talk to each other through music.

© James Gilchrist